Ambahan

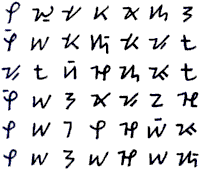

Ambahans inscribed on plants in a bamboo grove [Source: Antoon Postma]

The ambahan is the traditional poetry of the Hanunuo Mangyans of Oriental Mindoro. It is usually written on bamboo in the Surat Mangyan, a centuries-old pre-Spanish script. The syllabic script and the ambahan poetry have complemented each other, contributing to their continued existence today.

Reproduced here are three extracts from the work of Antoon Postma, anthropologist and Mangyan historian, and an ambahan anthology arranged according to the Hanunuo-Mangyan lifecycle.

Introduction to ambahan

The ambahan is a literary product and poetic expression of the Southern Mangyans of Mindoro, Philippines. Although there are about seven different ethnic groups living in Mindoro, collectively called the Mangyans, these groups are quite distinct from each other as to language, customs, and way of living. Only the ethnic group living in the south of Mindoro, roughly comprising the areas within the municipalities of Bulalacao (San Pedro), Mansalay, Oriental Mindoro and San Jose, Occidental Mindoro, claims the name Mangyan as the descriptive title of their tribe. To stress their point, they might add the epiteth: "Hanunuo" Mangyan, that is, a "truly, real, genuine" Manygan.

Together with their northern neighbors, the Buhids, they possess a pre-Spanish writing system, considered to be of Indic origin, with characters expressing the open syllables of the language. Two distinct syllabaries are still in practical use among the ethnic groups in Mindoro, viz. the northern Buhid on one hand and the southern Buhid with the Hanunuo-Mangyans on the other. The existence of a writing system among these tribes certainly accounts largely for the wealth of literature prevalent among them. One of the literary products, the one written down most frequently on bamboo-tubes or slats, is the ambahan.

For better understanding and appreciation of the ambahans presented here, a short outline on the character and use of the ambahan will be given here.

As a definition, it can be stated that the ambahan is:

- A rhythmic poetic expression with a meter of seven syllable lines and having rhythmic end-syllables.

- It is most often presented as a chant without a determined musical pitch or accompaniment by musical instruments.

- Its purpose is to express in an allegorical way, liberally using poetic language, certain situations or certain characteristics referred to by the one reciting the poem.

The meter of seven syllables in one line is the characteristic of the ambahan which most obviously distinguishes it from other kinds of Hanunuo-Mangyan poetry. However, there are exceptions to the rule. For instance, more than seven syllables may be found at the beginning of the ambahan, especially when it starts with the standard expression magkunkuno (speaks, says) because the one who "speaks" here may have a long name containing more than the usual seven syllables. Actually, these first lines should not be considered as part of the poem proper, but rather as an introduction to or an explanation of the circumstances which gave rise to the ambahan itself. Sometimes, there may be more than seven syllables because the employed word or words cannot be shortened and no other combination of words is available. On the other hand, a line may contain less than seven syllables in order to preserve the meaning of the line itself which might be disturbed if more syllables were added. However, the last exception rarely occurs.

In an effort to conform to the rule of having only seven syllables in each line, the composer tries to fit his words within the pre-determined quantity of syllables. This accounts for the many elisions and contactions of words that make the reading of the ambahan in the Hanunuo-Mangyan script so difficult and exasperating to the translator. Thus nirwasan comes from niruwasan; nilkasan from nilukasan; the mono-syllables gin from ginan; u from una. Conversely, the words may be extended, i.e. syllables may be added in order to have the required seven syllables. In most cases, the normal procedure involves the use of affixes and suffixes, both of which are extensively used in the Philippine languages. The most common one in the Hanunuo-Mangyan language is the suffix -an. Manok becomes manukan, balunos becomes balunusan, without a change in meaning. Within the word, "extensions" may also be found which might be old infixes, no longer common. So dayap becomes dalayap, layaw becomes lugayaw. Another way of lengthening a word is by repeating the word itself, not so much to make it superlative in meaning (e.g. in Tagalog: laking-laki), but rather to complete the seven syllable requirement.

While it is not my intention to be technical on this point, as a linguist's analysis of morphological phenomena would be, the foregoing illustrations demonstrate that the prescribed scheme of seven syllables in ambahan verse gives ample opportunity for lexical calisthenics, an exercise which may fascinate many students.

The rhyming end-syllables are an essential feature of the ambahan. The most common rhyming syllable is -an, being a regular suffix for verbs and substantives in the Hanunuo-Mangyan language. But other combinations with the vowel a are rather common too, such as in lines having the end-syllables: a, ak, ag, ang, as, aw, ay. Here the vowel a is combined with nearly all the consonants in the Philippine alphabet. In the same way, the vowels I (or e) and o (or u) can be found as the rhyming syllables, either alone or in combination, e.g.: I, id, ing, ip, it, and o, od, ok, on, ong, os, ot, oy.

The rhyming in the ambahan is consequent, i.e. once started with -an, all lines will end in -an. This appears to be in contrast to the rhyming scheme of a Tagalog poem, where at the end of a line a vowel rhyme may include any consonant in combination with this vowel. The ambahan is stricter in this respect, though it is interesting to note that here and there consonants, if belonging to the same phonetic class, may be included as the rhyming consonant in combination with the rhyming vowel. Hence, the word inwag rhymes with ma-ayad because both g and d belong to the phonetic class of voiced stops. The word humbak rhymes with dagat because both k and t belong to the phonetic class of voiceless stops. The word sundong, lumon and tayutom are the end-syllables of one ambahan because ng, n, and m belong to the phonetic class of voiced sonorants. Of course, it is not because the Hanunuo-Mangyan knows anything about phonetics that these instances occur, but it is a fact that the interchanges of these consonants are not considered violations of the unwritten rules of the ambahan, provided that the vowel remains the same.

The ambahan is a chanted verse, but it is changed plainly or almost recited. The rendering of the ambahan with musical pitch might differ from person to person. Some might intone the words like in common conversation; others might use it a monotone recitation; or still others might sing it with a distinct melody. But generally, it can be said that when an ambahan is "sung," there is only a slight musical pitch discernable, except maybe towards the end, when the last syllables are drawn out a bit to indicate that the chant is about to end. Furthermore, it is well worth noting that the ambahan, is "sung" without the accompaniment of musical instruments, as differentiated from another kind of Mangyan verse, the urukay, which is preferably chanted to the accompaniment of the homemade guitar.

One who has a knowledge of the language of the Hanunuo-Mangyans as it is used in their daily conversation, will be able to understand very little of the language that is used in the ambahan. The language used in the ambahan differs from the spoken language, though many a word used widely in the daily Hanunuo-Mangyan language is also used in the ambahan-vocabulary. It is quite possible to compile a long list of words (eventually a complete dictionary) that are used only in the ambahan verse, but, for the purpose of this book, only a few words need to be mentioned.

| Conversational language | Ambahan language | English |

|---|---|---|

| amang | bansay | father |

| inang | suyong | mother |

| danom | kagnan | water |

| balay | labag | house |

| niyog | bu-anay | coconut |

| bagaw | duyan | talk |

| mata | pamidkan | eye |

That the words of the ambahan vocabulary are found not only in the ambahan of the Hanunuo-Mangyans but also in the literary products of the neighboring Mangyan tribes, seems to be a significant coincidence worth investigating, especially if it is remembered that these other tribes use a conversational language different from the Hanunuo-Mangyan language. Some questions that would confront the investigator are the following: Where do these ambahan words come from? Are there other dialects in the Philippines from which they may have been derived? Or do we have to turn our attention to other countries like Indonesia or India to get an explanation? Here is a potential field of research that should give a linguist enough material to work on.

In some of the ambahans here presented, it will be noticed that the theme is about a bird, a flower, a tree, or an insect. Other ambahans, though not nature poems in the strict sense of the term, deal with the sun, the moon, the stars, the rain and the wind. When a Mangyan poet writes of a flower, he writes of itnot for the purpose of celebrating its beauty or fragrance but to make it an allegory or a symbol of human life, it's problems, and its challenges. Sometimes the symbolism of a bird or flower may be clear enough, as when a boy talks to his girl about "a beautiful flower that he would like to bring home." Very often, however, one symbol may refer to different conditions or circumstances and, thus, becomes a multiple symbol. An examination of ambahan no. 114 will help clarify this point. What does the poem mean? First, it means simply what it says: "Be careful, or you will be stung by a bee. Take precautions in getting honey." This would be the literal interpretation of the poem. The added meaning of allegorical interpretation would depend, of course, on the occasion and circumstances, such as climbing a mountain, going to sea, going to town, engaging in a contest with another person, or going to the parents to ask for the hand of their daughter. The complex set of meanings thus woven into an ambahan are gradually unravelled only after the poem had been analyzed with much care and patience.

A related study which is worth mentioning at this point would be an investigation into the psychological motivation for the Mangyan's frequent use of plants, animals, and nature symbols and their predilection for allegorical poetry.

[Postma, Antoon SVD. Treasure of a Minority. Manila: Arnoldus Press, Inc., 1981.]

The origin of the ambahan

A Hanunuo-Mangyan woman chanting an ambahan at a community ambahan session [Source: Antoon Postma]

If you ask a Hanunuo-Mangyan, "Where did you get this ambahan?," he will most likely answer, "I copied it from somebody else." That is quite probable, for the ambahan has been popularized by being copied on any piece of bamboo, such as the container for tobacco or apog (lime), the scabbard or sheath of a bolo, a violin or guitar, and even on the bamboo beams of a house. When a Mangyan discovers a nice ambahan, he uses his knife to engrave it on bamboo, in the age-old Indic-derived script. Thus, he has "copied" it.

In answer to the same question, another Mangyan may reply, "We obtained this from our forefathers." Most of the ambahans they possess now have been handed down from parents to children through continuos copying. Yet there is no doubt that new ambahans are still being written today by the poets or composers, although it is hard to find out who these poets are. A Mangyan would never admit that he is composing ambahans.

To determine the approximate time in which an ambahan was written, two criteria may be suggested: the subject and the kind of words used.

The first criterion cannot be applied without reservation, for the subject of the ambahan is sometimes very general and true of any period. But if we find reference in the ambahan to Moro attacks or to Mangyans still living along the sea-shore, we are on surer ground, for the attacks of the Moros are known to have occurred at a certain time, and the Mangyans lived along the shores before the non-Mangyans settled on the island. On the other hand, when an ambahan poet writes of going to America, the poem is certain to have been written in modern times.

The second criterion, the kind of words used, is more reliable and, if used by experts, would be a more certain indication of the age of the ambahan. By using this criterion, ambahans may be categorized into three classes.

The first type is the ambahan that only uses the poetic language with a minimum of contemporary words. Sometimes common Hanunuo-Mangyan words are used, but this type of ambahan restricts itself mainly to the use of literary words, i.e. words not used in daily conversation. According to the Mangyans themselves, this is the oldest kind of ambahan.

The next type of ambahan is that in which words borrowed from neighboring tribes, especially the Buhid tribe, are used. Frequent contact with this tribe has made the Hanunuo-Mangyans accept these borrowed words and expressions which found their way into their ambahans.

Lastly, there is the ambahan of later times, in which loan-words from Spanish, Tagalog or Bisaya are evident.

The painstaking study by linguists of the words used in the ambahan may supply the final answer to the question of the time in which an ambahan was written.

[Postma, Antoon. Mangyan Treasures. Manila: Arnoldus Press, Inc., 1995.]

The ambahan and its uses

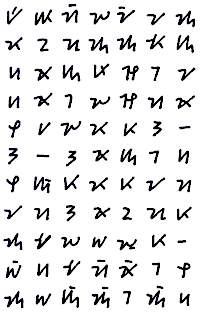

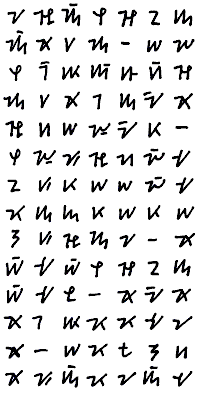

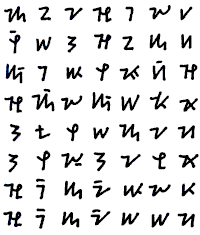

Hanunuo-Mangyan poems in the Mangyan syllabic script inscribed on betel nut containers made of bamboo

The ambahans are very common among the Hanunuo-Mangyans. About thirty percent of the Hanunuo-Mangyans do not read or write the pre-Spanish Hanunuo-Mangyan script, but it would be rare indeed for a Mangyan not to know the art of the ambahan. Of course, a Mangyan will quickly deny any knowledge of the ambahan, but this is only a polite way of refusing to demostrate such knowledge. People who have tried to collect ambahans will be the first to admit the difficulty of making the Mangyans recite the ambahans outside of the proper occasion for doing it.

Aside from the Hanunuo-Mangyans, the neighboring Mangyan tribes also know about the ambahan. Though the actual extent to which the ambahan is known by these other tribes has not been fully investigated, it is certain that this type of poetry is also common among the Buhid-Mangyans. The language of the Buhid is completely different from that of the Hanunuo-Mangyans, but one may still partly understand the literary products of the other. The ambahan can also be found among the tribes living deep in the mountains of Mindoro. These natives go down to the lowlands very rarely, and on one of these occassions I was lucky enough to acquire some copies of their ambahans. The Hanunuo-Mangyans do not understand much of it, except when exclusive ambahan words are used. However, before anything more authoritative can be said on this matter, one must explore the field further. The verse of the Iraya-Mangyans (in the north of Mindoro) is also very similar to the ambahan-type, i.e. they also have the characteristic heptasyllabic meter and rhyming end-syllables.

Ambahans are known and recited by Hanunuo-Mangyans, both old and young. Of course, different ambahans will be appropriate for different age groups.

The children definitely have their own kind of ambahans, something which might be considered as the equivalent of our nursery rhymes. However, even in these rhymes all the elements of the ambahan are present; the main distinction lies in the simplicity of the language used. The ambahans for children, however, are short, most of them containing not more than six lines.

A boy (kan-akan) and a girl (daraga) would be familiar with the ambahans fit for them, but once they are married, they would acquaint themselves with the ones that are appropriate for their new state of life.

Like all poetry, the ambahan is an expression of an idea or feeling in a beautiful and harmonious language. Unlike other forms of poetry , however, the ambahan is not poetry for its own sake or for the poet's satisfaction. The ambahan is primarily a poem of social character; it finds its true existence in society. It is created by the Mangyans to serve practical purposes within the community. It is used by the parents in educating their children, by young people in courting each other, by a visitor in asking for food and by a relative bidding goodbye or farewell. Of course, it would be a mistake to think that the Mangyans converse with each other only by the ambahan. If a man comes from his field, he would not use an ambahan to tell his wife that he is hungry; he will express the feeling of his stomach in plain and clear language. But generally speaking, the ambahan is used on those occasions when something embarrassing, unpleasant, delicate or even precious (as love) has to be said. For instance, a boy may tell a girl in plain language that he will never forget her, but it would sound so much nicer if he were to do so in an ambahan.

The social nature of the ambahan has given rise to a kind of verbal contest. Whenever Mangyans are together, a few of them (often the older generation) will eagerly compete with each other in the ability to recite the ambahan called for by the place and the occasion. Among these occasions are festivities held in connection with reburial. One Mangyan might challenge another with an ambahan, for example. This starts the contest. The people gather around the two contestants (without agreement, without rules, without bets), listening intently to the ambahans recited alternately by the two opponents. Each ambahan recited is an answer to the problem or theme propounded in the ambahan preceeding it. Both contestants are lustily cheered and encouraged by their supporters. In most cases, the one who recites last is declared the winner. The contest may go deep into the night. Whether one or the other wins is unimportant; what matters most is the entertainment derived from the contest.

A few final remarks about the translation of the ambahan may still be of interest. A researcher who happens to be in the mountains of Mansalay and becomes acquainted with the ambahan will become enthusiastic about it and may even want to translate some of them into his own language. But before he can translate the ambahan, he must study the ancient Indic script. After having mastered it well, he will find out to his dismay, that he still cannot read everything written on the bamboo. This is due to the fact that the script itself does not show the final consonant of each syllable. When he has overcome the disappointment, he will probably try to get an ambahan written down in clear, readable letters. Tape-recording the ambahan would take away the initial difficulties of copying from script. However, even then he will not understand all the implications of the ambahan unless the Mangyan can explain it.

In translating an ambahan, we find a special difficulty arising from the symbolic meaning of the words used. The Mangyan may supply the applied allegorical meaning but he might not understand the literal meanings of certain words. The meanings of these words can often be discovered because of the frequent use of repetition of ideas. Sometimes complete lines may be repetitions of the same idea in synonymous words.

Before the ambahan can be completely understood, it is imperative to collect as many samples of the ambahan as possible. This is the main work being done at present in this field. A detailed comparison of specimens, sifting and classifying words, and careful experiments in translating the words into another context have to be done by experts in this field of research. Only then will the ambahan emerge in the fullness of its beauty and signification.

The present anthology of ambahans is selected from a collection that started in 1958. In preparing this selection, it was not an easy task to decide on the best way of grouping or arranging these ambahans. It was finally decided to observe a dual system in classifying these Mangyan poems. The first system is to take the obvious and literal meaning as expressed by the poem. The second is the allegorical or applied meaning that can be gleaned from the ambahan. With this dual system in mind, the ambahans in this collection have been arranged according tot he life-cycle of the Hanunuo-Mangyans. Hence, this collection of ambahans starts with the cradle and ends with the grave. It is believed that this arrangement is the most satisfactory.

[Postma, Antoon SVD. Treasure of a Minority. Manila: Arnoldus Press, Inc., 1981.]

Ambahan: Birth and infancy

Since the aim of this collection of ambahans is to present a cross-section of the Mangyan poetic verse with respect to the life-cycle of the Mangyans, the first ambahans, to be chronological, should pertain to the first chapters of human life.

The following series of common cradle songs in ambahan style might be a fine illustration of how the songs can be different in rhyme and metaphor whereas the underlying theme is the same.

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

My dear baby, do not cry |

Huwag ka ngang umiyak |

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

Don't be noisy, baby dear! |

H'wag ka ngang magulo |

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

You, my baby, don't make noise! |

Anak, 'wag kang ngumalngal |

Ambahan: Childhood

Sweet are the memories of our childhood. For the Mangyan child, it is a time of unconcern and carefreeness, even if the child has to take his share of the family duties to the measure of his capacities. It is with feelings of sentimentality and homesickness that a young man recalls the happy years of his youth that passed away too fast. It is also with pride that he remembers the love and kindness shown to him by his parents.

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

That time, when I was still young, |

Noong ako'y muraan |

But there is also the obedient child who has his important task in the whole of the family work: watching that the products in the field will not be destroyed by the wild animals.

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

The reason why I am here, |

Sanhi po ng paglakad |

Children, however, are the same everywhere. Romping around with their playmates, they produce a deafening noise, often to the despair of their parents.

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

Sure, the kids they are not bad, |

Kahit bata'y mabait |

Ambahan: Adolescence

The transition from the dependent child into the self-sufficient young man or woman is not marked by initiation ceremonies or induction rites. In some things, children are given independence at an early age. In other things, they continue to act dependently.

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

Mother carried me around. |

Kinakalong ni Nanay |

Then the day comes when adolescence ends. The parents know now that there is not much hope that the young people will do things the way the parents want them to do. The young man goes his way, and nobody can direct him anymore.

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

Says the lobster in the creek: |

Sabi ng hipong sapa: |

The character of the youngster is fixed now. Even if there are traits the parents do not like, these traits can no longer be changed. Wherever he is, the young adult will behave in his accustomed manner and will not change his attitudes because of others.

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

Pigeon, with a shortened tail, |

Hoy, ibong Balud-balod |

Ambahan: Courtship

Many pages of sweet-flowing romances have been written about courtship, but the Mangyans create their own by using the examples of the budding and flowering plants and trees around them.

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

The bamboo in Marigit |

Kawayan sa Marigit |

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

The palm bordering my field |

Buli sa may kaingin |

A boy has his way of convincing a girl of his good intentions and intimate love. He is willing to sacrifice anything for his beloved.

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

My sweetheart, my love so dear, |

O liyag, aking hirang |

Ambahan: Home

To give a sample of all the various aspects of the home life within a Mangyan settlement would be next to impossible. However, an attempt to draw a general outline will be undertaken here. Two great themes can be considered of importance in the life-cycle of a Mangyan: 1) His struggle for life in and around his house, to keep hunger and sickness away; and, 2) His unbelievable ability to relax, be happy and unconcerned, often by escaping from his immediate surroundings.

What does a Mangyan home look like? His house is not as important as a house is to his countrymen of modern culture. A Mangyan will be the first to admit that his house is of poor construction and just a temporary dwelling.

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

This the forest Mangyan said: |

Sabi ng isang Mangyan: |

After all, life is hard and a Mangyan has to spend most of his time eking out a subsistence for himself, so the house itself is of little importance.

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

Your condition is quite good |

Dampa mo'y kainaman |

Even if the construction is nice and strong, the day will come that the house will be torn apart by the ripping blasts of wind.

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

Climbing vine with the long leaves, |

Hoy, uway na lambaan |

Ambahan: Problems

But at home, life is not always as pleasant as the Manygans would like it to be. There are dark days when the future doesn't look very bright. These dark days have to be overcome.

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

Balkawi, my climbing vine, |

Hoy, punong Balkawihan |

There are the domestic misunderstandings that might arise; the simple accidents that might happen.

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

Sticks from the balanti tree |

Kalutang kong Balanti |

There is no reason, however, to be as upset about a domestic misunderstanding or a simple accident as about a great disaster.

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

What is the matter with you |

Bakit ka nagkaganyan? |

Ambahan: Sickness

Sickness is unavoidable in human life. A person who is ill can easily be recognized. Sometimes, whatever is done, all treatment seems to be in vain. But there is always a treatment that's been forgotten.

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

This my problem, my headache, |

Itong ulong makirot |

A serious condition might develop. The usual treatments are of little help.

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

Says Yumay, when feeling ill: |

Panawagan ni Yumay |

Why don't the treatments work? Maybe all the requirements of offerings to the spirits were not properly fulfilled.

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

Says the spirit of the spring: |

Wika ng lamang-lupa |

Ambahan: Food and work

Obtaining food keeps the Mangyans busy for most of the year: selecting and preparing the field; sowing the carefully kept seed; weeding and cleaning the plants; harvesting the most precious food, cotton-white mountain rice. Unfortunately, an ideal harvest depends on an exact amount of sun, wind and rain. Often though, an extensive drought, a nasty typhoon or prolonged monsoon rains effect the opposite result, hardship and scarcity of food. It is therefore, no wonder that the Mangyans worry about their crops a great deal.

Rice is a food the Mangyans enjoy. After they have harvested their rice, it seems that there will never come an end to their supplies. But, before they realize it, gone is all their hope and happiness.

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

This kind of rice, Kabasag, |

Ang palay kong Kabasag |

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

The little black bird Sawi, |

Ibong si Sawi-sawi |

Whether one likes it or not, it is necessary to work hard in order to keep his stomach filled. He has to work hard even if he has the help of the spirits.

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

Our good and precious soil: |

Ating lupang payapa |

Ambahan: Traveling

As a relief from his struggle for life, the Mangyan sometimes goes traveling.

The moment will come when the Mangyan cannot be kept tied any longer to his house and the daily chores. He has to go, whether it is opportune or not. The woman, however, is not as fortunate as the man; she is tied to her home, especially when her children are still small. In spite of that, she would also like to go out once in a while. The parents should be, therefore, understanding and reasonable.

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

This journey that I must do, |

Iring aking pagpasyal |

The following ambahan is a special bit of advice to those with the unpleasant ringworm skin disease.

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

Little bird, Balinayaw, |

Ay naku ibong Balaw |

Just as the speed of those who travel differs, so the character also differs.

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

Take my bird, the bidlawan, |

Ibong kong si Bidlawan |

Ambahan: Hospitality and friendship

When a traveler arrives at a house he wont be afraid that he may not be welcome. Hospitality is considered the highest of virtues among the Mangyans.

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

My dear friend, be welcome here! |

Katoto kong matalik |

Sitting together on the balcony in the soft moonlight, the Mangyan feel inspired. Friendship is great!

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

Look! The moon so full and bright, |

Kay liwanag ng buwan |

The visitor will be home again, but the memory of his good friends will remain forever.

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

You, my friends, dearest of all, |

Lugod kong kaibigan |

Ambahan: Marriage

Although the courtship period has a varied set of rules and ceremonials, the marriage itself is as simple as possible. After the consent of the parents has been obtained, the unceremonial first sleep of both the spouses together is considered as wedlock itself.

In the ambahan literature, a major part revolves around the perennial theme of married life and all its ramifications. After many years of living together, does the husband still remember his promise that he gave as an ardent lover?

When difficulties arise, the Mangyans try to smooth them out themselves.

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

If the ties you use at home |

Panali ma'y marupok |

The following advice is worthwhile to remember!

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

Even with disharmony |

Kahit may kaguluhan |

Parting for a longer period of time is sad for the couple.

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

My dear fragrant herb, my wife, |

Kab'yak kong halimuyak |

Ambahan: Old age

Sharing their love, the happy couple grows old together.

Old age in Mangyan society is not given special status and special privileges. As long as anyone is able to keep up, he is expected to take part in daily work. It is, therefore, not surprising to see the old and feeble people working side by side with the younger generations in the rice fields. However, the irrevocable advance of time is felt by the elder generation. It is something that can't be changed.

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

It's a fact we all know, |

Di ba't totoo naman |

Among themselves, the older generation talk about the time when they will no longer be together. Will there still come another day after this night?

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

At this hour of the dark night |

Sa sandaling karimlan |

The thought of death is quietly accepted by a Mangyan. It is not the frightful and horrible event that is feared so much by the lowland Christians. For a Mangyan, death is part of the life cycle of every human being; it is looked upon as something that will bring a definite change in life, mostly for the better, not for the worst. Especially when the Mangyan gets old, he likes to think of death as the moment that will bring him back again to his beloved who went ahead of him.

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

Says the man, already old, |

Wika ng isang Mangyan |

Ambahan: Death

When physical life comes to an end, the soul departs for another place.

The moment of dying, this singular experience, is vividly remembered afterwards by the soul, especially if death came during an agonizing circumstance.

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

Says the soul remembering: |

Taghoy ng kaluluwa: |

Tragic, also is the Mangyan who died out of misery and chagrin because of the hardship he had to deal with! We do not know what his problems were or who caused them, but that he had some is clear from his explanation!

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

These are the words of the soul: |

Hinagpis ng kalul'wa: |

All this information comes from the realm of the dead, furnished by the deceased themselves! Communicating with the souls or spirits of the dead is nothing extraordinary for the Mangyans. These are those persons who possess the power to strike up a conversation with the spirits by means of a medium or daniw. The conversation resembles a séance among spiritualists.

The Mangyan who grieves about the death of a dear one likes to avail himself of the services of a daniw in order to see if the soul of the deceased cannot be convinced to come back and join his earthly body again. Positive results are said to be known, but they are not recorded in the ambahan verse. The ambahan samples available only relate the failure of the daniw and the decisiveness of the soul to continue his course in the other life.

| Hanunuo-Mangyan | English | Filipino |

|---|---|---|

|

Says the seer's medium: |

Ang wika nitong Daniw: |